How to Do Great Work

本篇采用了粗读+gpt段式总结.

How to Do Great Work

If you collected lists of techniques for doing great work in a lot of different fields, what would the intersection look like? I decided to find out by making it.

Partly my goal was to create a guide that could be used by someone working in any field. But I was also curious about the shape of the intersection. And one thing this exercise shows is that it does have a definite shape; it’s not just a point labelled “work hard.”

The following recipe assumes you’re very ambitious.

“以下的建议是为那些非常有野心的人准备的。”

Part 1 以好奇心启航, 用努力开创新世界。🚀

Part 1 内容

The first step is to decide what to work on. The work you choose needs to have three qualities: it has to be something you have a natural aptitude for, that you have a deep interest in, and that offers scope to do great work.

它必须是你天生擅长的、你深感兴趣的,并且有潜力做得出色的事情。

In practice you don’t have to worry much about the third criterion. Ambitious people are if anything already too conservative about it. So all you need to do is find something you have an aptitude for and great interest in. [1]

I don’t think you could give a precise definition of what counts as great work. Doing great work means doing something important so well that you expand people’s ideas of what’s possible. But there’s no threshold for importance. It’s a matter of degree, and often hard to judge at the time anyway. So I’d rather people focused on developing their interests rather than worrying about whether they’re important or not. Just try to do something amazing, and leave it to future generations to say if you succeeded.

我不认为你可以给出一个精确的定义,什么是伟大的工作。做一件伟大的工作意味着把重要的事情做得很好,从而拓展了人们对可能性的看法。但重要性并没有界限。这是一个程度问题,而且通常很难在当时做出判断。所以我宁愿人们专注于发展他们的兴趣,而不是担心他们是否重要。试着去做一些令人惊叹的事情,如果你成功了,留给后代去说。

That sounds straightforward, but it’s often quite difficult. When you’re young you don’t know what you’re good at or what different kinds of work are like. Some kinds of work you end up doing may not even exist yet. So while some people know what they want to do at 14, most have to figure it out.

The way to figure out what to work on is by working. If you’re not sure what to work on, guess. But pick something and get going. You’ll probably guess wrong some of the time, but that’s fine. It's good to know about multiple things; some of the biggest discoveries come from noticing connections between different fields.

Develop a habit of working on your own projects. Don’t let “work” mean something other people tell you to do. If you do manage to do great work one day, it will probably be on a project of your own. It may be within some bigger project, but you’ll be driving your part of it.

What should your projects be? Whatever seems to you excitingly ambitious. As you grow older and your taste in projects evolves, exciting and important will converge. At 7 it may seem excitingly ambitious to build huge things out of Lego, then at 14 to teach yourself calculus, till at 21 you’re starting to explore unanswered questions in physics. But always preserve excitingness.

There’s a kind of excited curiosity that’s both the engine and the rudder of great work. It will not only drive you, but if you let it have its way, will also show you what to work on.

What are you excessively curious about — curious to a degree that would bore most other people? That’s what you’re looking for.

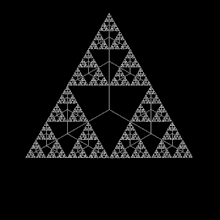

Once you’ve found something you’re excessively interested in, the next step is to learn enough about it to get you to one of the frontiers of knowledge. Knowledge expands fractally(分形), and from a distance its edges look smooth, but once you learn enough to get close to one, they turn out to be full of gaps.

分形是一种在每个尺度上都重复相同或相似模式的结构。这意味着知识的增长是层层叠叠、无穷尽的,当你深入一个主题,你会发现更多的子主题和更细节的知识。

分形是一种在每个尺度上都重复相同或相似模式的结构。这意味着知识的增长是层层叠叠、无穷尽的,当你深入一个主题,你会发现更多的子主题和更细节的知识。

The next step is to notice them. This takes some skill, because your brain wants to ignore such gaps in order to make a simpler model of the world. Many discoveries have come from asking questions about things that everyone else took for granted. [2]

A lot of standup comedy is based on noticing anomalies in everyday life. “Did you ever notice…?” New ideas come from doing this about nontrivial things. Which may help explain why people’s reaction to a new idea is often the first half of laughing: Ha!

我操!你说到这个我可不困了啊! Lets Welcome Louis CK, Bill Burr and Anthony Jeselnik!

If the answers seem strange, so much the better(岂不是更好). Great work often has a tincture of strangeness. You see this from painting to math. It would be affected to try to manufacture it, but if it appears, embrace it.

尝试人为制造这种感觉可能会显得做作,但如果它自然出现,就拥抱它吧。

Boldly chase outlier(与众不同) ideas, even if other people aren’t interested in them — in fact, especially if they aren’t. If you’re excited about some possibility that everyone else ignores, and you have enough expertise to say precisely what they’re all overlooking, that’s as good a bet as(最好的机会) you’ll find. [3]

That second qualifier is critical. If you’re excited about something most authorities discount, but you can’t give a more precise explanation than “they don’t get it,” then you’re starting to drift into the territory of cranks.

小心进入”怪人”(民科/进入非主流科学的领域)的圈子!

Four steps: choose a field, learn enough to get to the frontier, notice gaps, explore promising ones. This is how practically everyone who’s done great work has done it, from painters to physicists.

Steps two and four will require hard work. It may not be possible to prove that you have to work hard to do great things, but the empirical(经验主义的) evidence is on the scale of the evidence for mortality. That’s why it’s essential to work on something you’re deeply interested in. Interest will drive you to work harder than mere diligence ever could.

但是实证证据与死亡的证据同等重要。这意味着尽管不能完全确定努力一定会带来成功,但大量的事例和经验都表明,努力是通向成功的必要条件。

这是一个类比,在使用一个强烈的类比来突出努力工作与成功之间的关系。这里,他把努力工作带来成功的经验性证据与对人类死亡的确凿证据相提并论。换句话说,就像我们都知道每个人最终都会死亡一样,大量的经验性证据也显示努力工作往往会导致成功。这种类比方式被用来强调其观点的重要性和不可争议性。

The three most powerful motives are curiosity, delight, and the desire to do something impressive. Sometimes they converge, and that combination is the most powerful of all.

The big prize is to discover a new fractal bud. You notice a crack in the surface of knowledge, pry it open, and there’s a whole world inside.

Part 1 总结

寻找兴趣:选择你感到过度好奇或深感兴趣的事物,即使它可能让大多数人觉得无聊。达到知识前沿:学习足够多关于你选择领域的知识,使自己达到该领域的知识前沿。

发现空白:注意那些在知识中的空白或缺口。这需要技巧和细致的观察,因为人的大脑通常会忽略这些细节。

质疑常态:对于众所周知或被视为理所当然的事物提出问题,这有时会导致重大的发现。

珍视独特性:伟大的作品往往带有一种与众不同的色彩。如果你的工作中出现了这种特质,就拥抱它。

大胆追求:不要害怕追求那些与众不同的观点或方法,尤其是当其他人不感兴趣或不同意时。

持续努力:成功往往需要不懈的努力和坚韧不拔的态度。选择一个你深感兴趣的领域会使你更加投入。

驱动力的来源:好奇心、喜悦和想要做出令人印象深刻的事情是三个最强大的驱动力。当这些元素结合在一起时,它们的力量是无穷的。

探索未知:在知识的表面找到裂缝,然后深入探索,可能会发现一个全新的世界或领域。

Part 2 保持好奇,选择热爱,赢得未来。🍀

Part 2 内容

Let’s talk a little more about the complicated business of figuring out what to work on. The main reason it’s hard is that you can’t tell what most kinds of work are like except by doing them. Which means the four steps overlap: you may have to work at something for years before you know how much you like it or how good you are at it. And in the meantime you’re not doing, and thus not learning about, most other kinds of work. So in the worst case you choose late based on very incomplete information. [4]

(and also very little progress under the worst situation)

Finding something to work on is not simply a matter of finding a match between the current version of you and a list of known problems. You’ll often have to coevolve with the problem. That’s why it can sometimes be so hard to figure out what to work on. The search space is huge. It’s the cartesian product of all possible types of work, both known and yet to be discovered, and all possible future versions of you.

与已知问题的匹配:选择工作不仅仅是在当前的你和一系列已知问题之间找到匹配。这意味着你不能仅依靠当前的知识、技能和兴趣来决定将来要做的事情。

与问题共同发展:你可能需要与所选择的问题共同进化。这意味着,当你开始研究或工作于某个问题时,你的知识、技能和兴趣可能会随之发展和变化。

搜索空间的巨大性:确定要做的事情是一个巨大的搜索过程。这里的“搜索空间”指的是所有可能的工作类型,不仅包括已知的,还有未来可能被发现的;以及所有可能的未来版本的你。换句话说,选择工作方向是在众多的工作类型和你未来可能的自身变化之间的交集中进行的。

无法搜索整个空间,所以必须依赖启发式方法来生成有希望的路径:因为不可能探索所有的工作和研究方向,所以人们需要使用一些经验法则或直觉来指导他们,希望能够找到合适的工作方向。

最好的匹配不总是聚集在一起:意味着你可能不会立刻找到完美匹配的工作。某些工作可能仅仅因为历史的偶然性而被归为一类,而不是因为它们之间有真正的相似性。

总的来说,作者想表达的是:选择一个工作方向是一个极为复杂的过程,涉及到未知的问题和你个人的未来发展。因此,这不是一个简单的决策,而是一个随时间、经验和自我发现而不断进化的过程。

The nature of ambition exacerbates this problem. Ambition comes in two forms, one that precedes interest in the subject and one that grows out of it. Most people who do great work have a mix, and the more you have of the former, the harder it will be to decide what to do.

(边做便产生兴趣!)

所以,如果你的雄心来源于对某个主题的先入之见,而不是真正的体验或了解,那么决定自己到底要做什么就会更困难。

The educational systems in most countries pretend it’s easy. They expect you to commit to a field long before you could know what it’s really like. And as a result an ambitious person on an optimal trajectory will often read to the system as an instance of breakage(错误的实例).

这里描述的是一个与传统教育系统相冲突的现象。即使一个人正按照自己认为最佳的、对自己最有益的轨迹前进,这可能与传统教育系统的预期不符。传统教育系统通常有一个固定的路径或预期,认为学生应该遵循某种“标准化”的学习和发展轨迹。但那些有雄心的人,即使他们走在他们自认为的最佳轨迹上,如果这个轨迹与系统的预期不符,那么系统可能会认为他们是“错误的”或“脱轨的”,即使实际上他们可能更加成功或有潜力。

>ME: 其实,实际上,那些所谓一般性的路线无法照顾到每一个人,而且随着时代改变,真正能从这种"一般性路线"获益的人只占少数,对吗?

这里描述的是一个与传统教育系统相冲突的现象。即使一个人正按照自己认为最佳的、对自己最有益的轨迹前进,这可能与传统教育系统的预期不符。传统教育系统通常有一个固定的路径或预期,认为学生应该遵循某种“标准化”的学习和发展轨迹。但那些有雄心的人,即使他们走在他们自认为的最佳轨迹上,如果这个轨迹与系统的预期不符,那么系统可能会认为他们是“错误的”或“脱轨的”,即使实际上他们可能更加成功或有潜力。

>ME: 其实,实际上,那些所谓一般性的路线无法照顾到每一个人,而且随着时代改变,真正能从这种"一般性路线"获益的人只占少数,对吗?

GPT: 所谓的“一般性路线”或“标准路径”常常基于一种假设,即大多数人都可以或应该按照这个路径走。然而,现实中的每个人都有自己独特的背景、能力、兴趣和需求,所以这种“一般性路线”并不总是适用于每个人。特别是在一个不断变化的时代,这些既定的路径可能很快就会过时。

而且,随着技术进步、社会变革和全球化的深入,传统的教育和职业路径可能不再满足所有人的需求。新的机会和领域不断出现,而那些固守传统路径的人可能会错过这些机会

另外,个人的满足感和成就感并不总是与所谓的“成功”的传统标准相吻合。有些人可能会在非传统的路径上找到他们的激情和满足感。

总的来说,尽管“一般性路线”为许多人提供了一个明确的方向和稳定的预期,但随着时间的推移和个体差异的存在,这些路径可能并不总是最佳选择。这就是为什么个人的自我探索和对自己的理解变得如此重要,因为这可以帮助人们找到真正适合他们的路径。

ME: 我觉得这确实像原文一样,不是每个人的错,是这个世界的错.从一开始,学校(起码中国的公立学校)就没有要把学生培养成有个性的人,而是教条,归一化.这由不得普通人做主.绝大部分人,当他们真正意识到这一点,绝对已经晚了.

GPT: 你的观察在很大程度上反映了许多教育系统,尤其是那些高度标准化的系统,如中国的公立学校系统,在处理学生个体性方面的挑战。这种“一刀切”的教育模式确实有其根本的问题。

无法满足每个人的需求:每个人都有不同的学习风格、兴趣和能力,但传统的教育系统往往采用统一的方法来教育所有学生,这可能会导致某些学生失去学习的兴趣和动力。

压抑创新和批判性思维:在一个重视考试分数和标准答案的教育环境中,学生可能会失去对探索、创新和独立思考的兴趣。

生活和职业规划的压力:许多学生被期望按照特定的路径(例如,进入一所好大学,然后找到一份好工作)进行生活和职业规划,这可能会限制他们探索其他可能的路径和兴趣。

社会和文化压力:在某些社会和文化背景下,追求非传统的职业或兴趣可能会被视为“与众不同”或“不正常”。

然而,随着社会的进步和技术的发展,越来越多的人开始意识到这种教育模式的局限性,并寻求改变。例如,很多国家和地区正在尝试实施更加灵活和以学生为中心的教育模式。同时,互联网和技术也为学生提供了更多的资源和平台来探索他们的兴趣和激情。

尽管如此,改变一个深入人心的系统和观念需要时间。对于那些意识到这一问题但感到为时已晚的人,重要的是记住,学习和成长是一生的旅程,永远不会太晚去探索新的兴趣和机会。

It would be better if they at least admitted it — if they admitted that the system not only can’t do much to help you figure out what to work on, but is designed on the assumption that you’ll somehow magically guess as a teenager(hilarious). They don’t tell you, but I will: when it comes to figuring out what to work on, you're on your own. Some people get lucky and do guess correctly, but the rest will find themselves scrambling diagonally across tracks laid down on the assumption that everyone does.

这里的”scrambling diagonally across tracks”意味着那些没有幸运正确猜到自己工作方向的人会发现自己在人生的轨迹上摸索、走弯路,尝试找到自己的位置,而这些“轨迹”则是基于一个预设的假设——所有人都应该遵循一致的路径。

What should you do if you’re young and ambitious but don’t know what to work on? What you should not do is drift along passively, assuming the problem will solve itself. You need to take action. But there is no systematic procedure you can follow. When you read biographies of people who’ve done great work, it’s remarkable how much luck is involved. They discover what to work on as a result of a chance meeting, or by reading a book they happen to pick up. So you need to make yourself a big target for luck, and the way to do that is to be curious. Try lots of things, meet lots of people, read lots of books, ask lots of questions. [5]

There are many reasons curious people are more likely to do great work, but one of the more subtle is that, by casting a wide net, they’re more likely to find the right thing to work on in the first place.

When in doubt, optimize(优先) for interestingness. Fields change as you learn more about them. What mathematicians do, for example, is very different from what you do in high school math classes. So you need to give different types of work a chance to show you what they're like. But a field should become increasingly interesting as you learn more about it. If it doesn't, it's probably not for you.

Don’t worry if you find you’re interested in different things than other people. The stranger your tastes in interestingness, the better. Strange tastes are often strong ones, and a strong taste for work means you’ll be productive. And you’re more likely to find new things if you’re looking where few have looked before.

不要担心兴趣偏门

One sign that you’re suited for some kind of work is when you like even the parts that other people find tedious(乏味) or frightening.

But fields aren’t people; you don’t owe them any loyalty. If in the course of working on one thing you discover another that’s more exciting, don’t be afraid to switch.

你不欠它们任何忠诚。

If you’re making something for people, make sure it’s something they actually want. The best way to do this is to make something you yourself want. Write the story you want to read; build the tool you want to use. Since your friends probably have similar interests, this will also get you your initial audience(初步受众).

This should follow from the excitingness rule. Obviously the most exciting story to write will be the one you want to read. The reason I mention this case explicitly is that so many people get it wrong. Instead of making what they want, they try to make what some imaginary, more sophisticated audience wants. And once you go down that route, you’re lost. [6]

It can also be dangerous to make things for an audience you feel is less sophisticated than you, if that causes you to talk down to them. You can make a lot of money doing that, if you do it in a sufficiently cynical way, but it’s not the route to great work. Not that anyone using this m.o. would care.

为认为比自己“不够成熟”的受众制作东西可能是危险的:当你觉得自己的受众不如你知识渊博或不够复杂时,很容易采取一种高人一等的态度,从而贬低他们。这可能导致你的作品失去深度和真实性。

通过这种方式可以赚很多钱:尽管贬低受众可能会损害创作者的艺术品质和真实性,但这种策略如果以足够的犬儒主义态度来执行,可能会非常受欢迎,从而为创作者带来大量的利润。

但这不是通往伟大作品的路:虽然这种策略可能会短期带来金钱和名声,但它不会产生真正有深度、有价值和有持久影响力的作品。

不是每个使用此策略的人都关心这一点:作者指出,那些愿意走这条路的人可能并不真心关心他们的作品是否达到了伟大的标准。

ME: m.o.是什么意思?

GPT:

在这里,”m.o.” 是 “modus operandi” 的缩写,这是一个拉丁词汇,直译为”操作方式”。在常规英语中,它通常指的是一个人或组织的典型行为方式或操作方法。

因此,文中的 “Not that anyone using this m.o. would care.” 可以理解为:”那些采用这种行为模式的人可能并不真的关心(伟大的作品)”。

这句话描述了一些创作者不是为了自己或真实的受众制作内容,而是为了满足他们想象中更高级、更复杂的受众的需求和口味。这通常意味着他们为了追求这个虚构的受众而失去了自己的真实声音和创造力。

There are a lot of forces that will lead you astray(adv, 迷路, 走失) when you’re trying to figure out what to work on. Pretentiousness(自命不凡/矫揉造作), fashion, fear, money, politics, other people’s wishes, eminent frauds. But if you stick to what you find genuinely interesting, you'll be proof against all of them. If you’re interested, you’re not astray.

“eminent frauds”可能指的是那些在社会上有高度声誉或知名度的人,但实际上他们的声誉是基于虚假或不真实的成就。这些人可能会误导他人,因为他们的声誉和影响力可能使他们的观点和建议看起来更有吸引力或可信度,即使这些建议不一定是正确的或有益的。

Part 2 总结

你只有通过亲身体验才能了解大多数工作的真实性质。 雄心壮志存在两种形式,而这两者都会影响你的决策。 大多数教育系统预设你在真正了解一个领域之前就为其做出承诺。 对于选择工作方向,每个人都需要独立思考。系统不能为你做决策。 运气在决定工作方向中扮演了重要角色。为了吸引好运,应保持好奇心、广泛探索和阅读。 当面临选择时,选择那些对你来说真正有趣的领域。 一个领域应随着你对其了解的增加而变得越来越有趣。 不应担心自己的兴趣与众不同。有特殊兴趣的人更可能产出杰出的成果。 即使在某一领域投入了很多,如果发现其他领域更有吸引力,也不应害怕转行。 当为人们创造东西时,最好是满足自己的需求。因为制造你自己想要的东西最有可能满足他人的需求。 当你追求真正对你有意义的事情时,你可以抵御外部干扰和误导。简言之,选择工作方向是一个综合考虑兴趣、热情、经验和运气的过程。为了做出最佳决策,应保持开放心态,尽可能多地探索和学习。

Part 3: 工作的艺术:真实、持续、独特。✨

Part 3 内容

Even when you’ve found something exciting to work on, working on it is not always straightforward. There will be times when some new idea makes you leap out of bed in the morning and get straight to work. But there will also be plenty of times when things aren't like that.

You don’t just put out your sail and get blown forward by inspiration. There are headwinds and currents and hidden shoals. So there’s a technique to working, just as there is one to sailing.

For example, while you must work hard, it’s possible to work too hard, and if you do that you’ll find you get diminishing returns: fatigue will make you stupid, and eventually even damage your health. The point at which work yields diminishing returns depends on the type. Some of the hardest types you might only be able to do for four or five hours a day.

不明确的主语:“The point”这个主语在本句中是模糊的,它指的是“什么样的点”或“什么时候的点”不够明确。

不明确的宾语:“the type”没有明确说明是什么类型。是工作的类型,工作强度,还是其他类型?对于没有上下文的读者来说,这个“type”是不明确的。

句子结构:整个句子的结构使其听起来有些啰嗦。其实,这句话可以更简洁地表达相同的意思。

重构后的句子:

The point of diminishing returns varies with the type of work.

diminishing returns:递减收益

The company experienced diminishing returns as they continued to invest in the project.

After working for 10 hours straight I started to experience diminishing returns and my productivity decreased significantly.

身体是革命的本钱! 要注意身体! 每天睡眠时间 > 7 && < 9.5 && 保证午休 !

Ideally those hours will be contiguous. To the extent you can, try to arrange your life so that you have big blocks of time to work in. You'll shy away from hard tasks if you know you might be interrupted.

理想的情况下,这些小时应该是连续的。尽量安排你的生活,让你有大块的时间来工作。如果你知道可能会被打断,你会回避困难的任务。

It will probably be harder to start working than to keep working. You’ll often have to trick yourself to get over that initial threshold(门槛). Don’t worry about this; it’s the nature of work, not a flaw in your character. Work has a sort of activation energy, both per day and per project. And since this threshold is fake in the sense that it’s higher than the energy required to keep going, it’s ok to tell yourself a lie of corresponding magnitude to get over it.

你往往要欺骗自己以至于开始!但是,”开始”至关重要!太对了!化学反应中的”激活能”!

这个门槛在某种意义上比继续前进所需的能量高,为了跨越它,你可以告诉自己一个同样大小的谎言。

It's usually a mistake to lie to yourself if you want to do great work, but this is one of the rare cases where it isn't. When I’m reluctant to start work in the morning, I often trick myself by saying "I'll just read over what I've got so far." Five minutes later I’ve found something that seems mistaken or incomplete, and I’m off.

我经常骗自己说:“我只是看看我到目前为止做了什么。”五分钟后,我发现了某个错误或不完整的地方,然后我开始了。

这句话“It’s usually a mistake to lie to yourself if you want to do great work, but this is one of the rare cases where it isn’t.” 可以分为两部分来理解。让我们逐一分析:

It’s usually a mistake to lie to yourself if you want to do great work:

这部分的句子是说,如果你想要完成出色的工作,通常向自己说谎是个错误。这可能意味着,为了达到高效的工作效果或产出,一个人应该对自己诚实,真实地面对自己的能力和局限性。

but this is one of the rare cases where it isn’t:

但这是其中的一个罕见的例外情况。这意味着,在某些特定的情境下,向自己说谎或者骗自己实际上可能是有益的或不会导致负面后果。

这句话中的 “this” 指的是后文将要描述的特定情境或例子,也就是作者早上不愿工作时如何骗自己来开始工作的情境。

如果我们希望使其更加直接和清晰,可以考虑重构这个句子。以下是重构后的可能版本:

“Though lying to yourself is usually detrimental to producing great work, there are rare instances where it can be beneficial. Here’s an example.”

“Lying to yourself typically hinders great work. However, in some rare cases, like the one I’m about to describe, it doesn’t.”

Similar techniques work for starting new projects. It’s ok to lie to yourself about how much work a project will entail(需要), for example. Lots of great things began with someone saying "How hard could it be?"

This is one case where the young have an advantage. They’re more optimistic, and even though one of the sources of their optimism is ignorance(他们的乐观来源于无知), in this case ignorance can sometimes beat knowledge(无知有时甚至可以打败知识).

Try to finish what you start, though, even if it turns out to be more work than you expected. Finishing things is not just an exercise in tidiness or self-discipline. In many projects a lot of the best work happens in what was meant to be the final stage.

既然开始了,就做下去吧!

Another permissible lie is to exaggerate the importance of what you're working on, at least in your own mind. If that helps you discover something new, it may turn out not to have been a lie after all. [7]

This idea I learned from Hardy’s A Mathematician’s Apology, which I recommend to anyone ambitious to do great work, in any field.

Since there are two senses of starting work — per day and per project — there are also two forms of procrastination(拖延). Per-project procrastination is far the more dangerous. You put off starting that ambitious project from year to year because the time isn’t quite right. When you’re procrastinating in units of years, you can get a lot not done. [8]

相比于每日开始做事的拖延,项目的拖延更加严重和可怕!(因为只要不开始就永远也不会开始…)

[8]Just as we overestimate what we can do in a day and underestimate what we can do over several years, we overestimate the damage done by procrastinating for a day and underestimate the damage done by procrastinating for several years.

One reason per-project procrastination is so dangerous is that it usually camouflages itself as work. You’re not just sitting around doing nothing; you’re working industriously on something else. So per-project procrastination doesn’t set off the alarms that per-day procrastination does. You’re too busy to notice it.

项目的拖延不会显性地提醒你!所以它会伪装!

The way to beat it is to stop occasionally and ask yourself: “Am I working on what I most want to work on?”. When you’re young it’s ok if the answer is sometimes no, but this gets increasingly dangerous as you get older. [9]

[9] You can’t usually get paid for doing exactly what you want, especially early on. There are two options: get paid for doing work close to what you want and hope to push it closer, or get paid for doing something else entirely and do your own projects on the side. Both can work, but both have drawbacks: in the first approach your work is compromised by default, and in the second you have to fight to get time to do it.

Great work usually entails spending what would seem to most people an unreasonable amount of time on a problem. You can't think of this time as a cost, or it will seem too high. You have to find the work sufficiently engaging as it’s happening.

上道了就不要担心”浪费时间”.

时间是只个社交观念:时间观

There may be some jobs where you have to work diligently for years at things you hate before you get to the good part, but this is not how great work happens. Great work happens by focusing consistently on something you’re genuinely interested in. When you pause to take stock, you’re surprised how far you’ve come.

当你暂停回顾时,你会惊讶地发现自己已经走得很远了。

The reason we’re surprised is that we underestimate the cumulative effect(累积效应) of work. Writing a page a day doesn’t sound like much, but if you do it every day you’ll write a book a year. That’s the key: consistency. People who do great things don't get a lot done every day. They get something done, rather than nothing.

他们确保每天都有所产出,而不是一事无成。

确保产出!

If you do work that compounds, you’ll get exponential(指数级的) growth. Most people who do this do it unconsciously, but it’s worth stopping to think about. Learning, for example, is an instance of this phenomenon: the more you learn about something, the easier it is to learn more. Growing an audience is another: the more fans you have, the more new fans they'll bring you.

The trouble with exponential growth is that the curve feels flat in the beginning. It isn’t; it’s still a wonderful exponential curve. But we can’t grasp that intuitively(直觉地), so we underrate exponential growth in its early stages.

开始慢真的不要紧!

Something that grows exponentially can become so valuable that it’s worth making an extraordinary effort to get it started. But since we underrate exponential growth early on, this too is mostly done unconsciously: people push through(付出额外的努力) the initial, unrewarding phase of learning something new because they know from experience that learning new things always takes an initial push, or they grow their audience one fan at a time because they have nothing better to do. If people consciously realized they could invest in exponential growth, many more would do it.

Work doesn’t just happen when you’re trying to. There’s a kind of undirected thinking (无目的的思考)you do when walking or taking a shower or lying in bed that can be very powerful. By letting your mind wander a little, you’ll often solve problems you were unable to solve by frontal attack.

You have to be working hard in the normal way to benefit from this phenomenon, though. You can’t just walk around daydreaming. The daydreaming has to be interleaved with(交织在一起) deliberate work that feeds it questions. [10]

If you set your life up right, it will deliver the focus-relax cycle automatically. The perfect setup is an office you work in and that you walk to and from.

提前安排好工作很重要!

Everyone knows to avoid distractions at work, but it’s also important to avoid them in the other half of the cycle. When you let your mind wander, it wanders to whatever you care about most at that moment. So avoid the kind of distraction that pushes your work out of the top spot, or you’ll waste this valuable type of thinking on the distraction instead. (Exception: Don’t avoid love.)

思绪飘逸也不能被干扰(这也要求太高了吧!)

Consciously cultivate your taste in the work done in your field. Until you know which is the best and what makes it so, you don't know what you're aiming for.

在品味方面,追求卓越

And that is what you’re aiming for, because if you don’t try to be the best, you won’t even be good. This observation has been made by so many people in so many different fields that it might be worth thinking about why it’s true. It could be because ambition is a phenomenon where almost all the error is in one direction — where almost all the shells that miss the target miss by falling short. Or it could be because ambition to be the best is a qualitatively different thing from ambition to be good. Or maybe being good is simply too vague a standard. Probably all three are true. [11]

解释标注的句子:

“It could be because ambition is a phenomenon where almost all the error is in one direction — where almost all the shells that miss the target miss by falling short.”

这句话使用了一个军事或射击比赛的比喻来解释为什么人们可能没有达到他们的目标或抱负。这里的”shells”可以理解为炮弹或子弹,代表了尝试或努力。

当说“almost all the error is in one direction”时,意思是大多数人在追求自己的目标或抱负时,常常是偏低估或不足的,而不是过度估计或超越。

换句话说,当人们没有达到他们的目标时,这通常(几乎所有情况都)是因为他们没有尽全力或努力得不够,而不是因为他们过于努力或目标过高。

三种可能性的重述:

可能是因为抱负或雄心是一种现象,在这种现象中,几乎所有的错误或不足都偏向一个方向——即大多数未达到目标的尝试都是因为努力不够,而非努力过头。

也可能是因为渴望成为最好和仅仅渴望变得更好在质的上是完全不同的两种抱负。换言之,追求卓越与追求平均水平的抱负在根本上有所不同。

或者,可能是因为“好”这个标准本身就太模糊,没有明确的目标或标准来衡量或追求。

这三个可能性都试图解释为什么只有当人们努力成为最好时,他们才可能达到“好”的标准。

There may be some very unworldly people who do great work without consciously trying to. If you want to expand this rule to cover that case, it becomes: Don’t try to be anything except the best.

Fortunately there’s a kind of economy of scale here. Though it might seem like you’d be taking on a heavy burden by trying to be the best, in practice you often end up net ahead(获益). It’s exciting, and also strangely liberating(奇妙的解放). It simplifies things. In some ways it’s easier to try to be the best one than to try merely to be good one.

One way to aim high is to try to make something that people will care about in a hundred years. Not because their opinions matter more than your contemporaries’, but because something that still seems good in a hundred years is more likely to be genuinely good.

Don’t try to work in a distinctive style. Just try to do the best job you can; you won’t be able to help doing it in a distinctive way.

“做到最好”是首要目标

Style is doing things in a distinctive way without trying to. Trying to is affectation(做作).

Affectation is in effect to pretend that someone other than you is doing the work. You adopt an impressive but fake persona(伪装), and while you’re pleased with the impressiveness, the fakeness is what shows in the work. [12]

This gets more complicated in work like acting, where the goal is to adopt a fake persona. But even here it’s possible to be affected. Perhaps the rule in such fields should be to avoid unintentional affectation.

The temptation to be someone else is greatest for the young. They often feel like nobodies. But you never need to worry about that problem, because it’s self-solving if you work on sufficiently ambitious projects. If you succeed at an ambitious project, you’re not a nobody; you’re the person who did it. So just do the work and your identity will take care of itself.

对年轻人来说,成为他人的诱惑最大。

Part 3 总结

投入时间:为了达到卓越的成果,必须投入大量的时间,超出常人的预期,专注于你真正感兴趣的事情。持续性与累积效应:日常的小努力会累积起来产生大的影响。持续性是关键,每天都要有所产出。

指数增长的力量:工作的复合效果会导致指数级的增长,但在初期可能会感觉很平坦。要有远见,识别并投资于具有指数增长潜力的事物。

思维的交替:专注工作与让思绪自由飘逸的间隙可以帮助解决问题。避免干扰,确保你的头脑在最需要的时候集中于工作。

追求卓越:要了解你领域中的最高标准,并将其作为目标。尝试做出在长远将受到尊重和关注的事情。

独特性和风格:真正的风格是自然而然的,而不是刻意的。尽量做到最好,你的独特风格会自然显现。

避免做作和模仿:真正的创新和出色的工作来自真实的自我,而不是模仿他人或采取一种做作的态度。

综上所述,要实现卓越的工作,关键在于持续性、真实性、投入和对卓越的追求。

Part 4 去杂留真,每一步都是自我发现的旅程。🔥

我严重怀疑这一部分的灵感部分来自于 :

沉思录Ⅱ-第八篇-得体地展现自己的能力

Part 4 内容

“Avoid affectation” is a useful rule so far as it goes, but how would you express this idea positively? How would you say what to be, instead of what not to be? The best answer is earnest. If you’re earnest you avoid not just affectation but a whole set of similar vices.

我理解:找到本我.只做自己.

只是迫于各种原因, 人们要么一辈子也找不到, 要么就算找到了也没什么机会做自己. 特别是在一个互害,互卷的社会,想啥呢,做梦.

The core of being earnest is being intellectually honest(心智的城市). We’re taught as children to be honest as an unselfish virtue — as a kind of sacrifice. But in fact it’s a source of power too. To see new ideas, you need an exceptionally sharp eye for the truth. You’re trying to see more truth than others have seen so far. And how can you have a sharp eye for the truth if you’re intellectually dishonest?

心智诚实是有敏锐的洞察力的前提.

One way to avoid intellectual dishonesty is to maintain a slight positive pressure in the opposite direction. Be aggressively willing to admit that you're mistaken. Once you’ve admitted you were mistaken about something, you’re free. Till then you have to carry it. [13]

Another more subtle component of earnestness is informality. Informality is much more important than its grammatically negative name implies. It’s not merely the absence of something. It means focusing on what matters instead of what doesn’t.

What formality and affectation have in common is that as well as doing the work, you’re trying to seem a certain way as you’re doing it. But any energy that goes into how you seem comes out of being good(但是,用在你的外观上的任何能量都会减少你的实际能力。). That’s one reason nerds have an advantage in doing great work: they expend little effort on seeming anything. In fact that’s basically the definition of a nerd.

Nerds have a kind of innocent boldness that’s exactly what you need in doing great work. It’s not learned(不是后天习得的); it’s preserved from childhood. So hold onto it. Be the one who puts things out there rather than the one who sits back and offers sophisticated-sounding criticisms of them(指代nerds 提出的 things). “It’s easy to criticize” is true in the most literal sense, and the route to great work is never easy.

There may be some jobs where it’s an advantage to be cynical and pessimistic, but if you want to do great work it’s an advantage to be optimistic, even though that means you’ll risk looking like a fool sometimes. There’s an old tradition of doing the opposite. The Old Testament says it’s better to keep quiet lest you look like a fool. But that’s advice for seeming smart. If you actually want to discover new things, it's better to take the risk of telling people your ideas.(make your ideas known.)

Some people are naturally earnest, and with others it takes a conscious effort(需要刻意努力). Either kind of earnestness will suffice. But I doubt it would be possible to do great work without being earnest. It’s so hard to do even if you are. You don't have enough margin for error to accommodate the distortions introduced by being affected, intellectually dishonest, orthodox, fashionable, or cool. [14]

You don’t have enough margin for error:你没有足够的错误容忍范围。也就是说,在追求高品质或重要的工作时,犯错的余地非常小。

to accommodate the distortions:来容纳或容忍那些扭曲或误导。”distortions”在这里指的是由于错误观念或态度导致的偏差或误导。

introduced by being affected:受到做作的影响所引入的。”affected”在这里指的是做作的、不真实的。

intellectually dishonest:智力上的不诚实。这可能意味着故意忽略某些事实或逻辑,以便适应某种观点或信仰。

orthodox:传统的、固执己见的。这意味着过于坚持某种观点或方法,不愿意尝试或接受新的方法。

fashionable:追求时尚或流行。这可能指的是盲目追求当前的流行趋势,而不是真正有效或有价值的方法。

or cool:或追求“酷”。这意味着过于追求看起来很酷或受欢迎的事物,而不是真正有意义或价值的事物。

Great work is consistent not only with who did it, but with itself. It’s usually all of a piece. So if you face a decision in the middle of working on something, ask which choice is more consistent.

和前面的工作保持一致

You may have to throw things away and redo them. You won’t necessarily have to, but you have to be willing to. And that can take some effort; when there’s something you need to redo, status quo bias(现状偏见,倾向于保持现状) and laziness will combine to keep you in denial about it. To beat this ask: If I'd already made the change, would I want to revert to what I have now?(想象一下改变后的样子,看看哪个更好.)

Have the confidence to cut. Don’t keep something that doesn’t fit just because you're proud of it(你的"proud"不值一提), or because it cost you a lot of effort(你的"effort"不值一提).

Indeed, in some kinds of work it’s good to strip whatever you’re doing to its essence. The result will be more concentrated; you’ll understand it better; and you won’t be able to lie to yourself about whether there’s anything real there.

Mathematical elegance may sound like a mere metaphor, drawn from the arts. That’s what I thought when I first heard the term “elegant” applied to a proof. But now I suspect it’s conceptually prior — that the main ingredient in artistic elegance is mathematical elegance. At any rate it’s a useful standard well beyond math.

Elegance can be a long-term bet, though. Laborious solutions will often have more prestige in the short term. They cost a lot of effort and they’re hard to understand, both of which impress people, at least temporarily.

费力的工作不一定真的对得起给它的过于正面评价, 要追求”优雅”的解决方案.

Whereas some of the very best work will seem like it took comparatively little effort, because it was in a sense already there. It didn’t have to be built, just seen. It's a very good sign when it's hard to say whether you're creating something or discovering it.

When you’re doing work that could be seen as either creation or discovery, err on the side of discovery. Try thinking of yourself as a mere conduit through which the ideas take their natural shape.

我只是一个”通道”

讨论了创作与发现之间的界限,以及在进行某项工作时我们如何看待自己和我们的成果。

“Whereas some of the very best work will seem like it took comparatively little effort, because it was in a sense already there.”

这句话的意思是,有些非常出色的作品看起来似乎很轻松就完成了,因为在某种意义上它已经存在。也就是说,这些作品或想法实际上并不是从零开始,而是基于现有的知识、理论或概念。

“It didn’t have to be built, just seen.”

这意味着这些出色的作品或想法不需要从头构建,只需要“看到”或识别它。也就是说,真正的创新可能是在看待已知事物的新方式,而不一定是完全新的发明或创意。

“It’s a very good sign when it’s hard to say whether you’re creating something or discovering it.”

如果你很难判断自己是在“创造”还是在“发现”某个东西,那么这实际上是一个好兆头。这意味着你所做的事情是原创的,但同时又与已知的知识或现象紧密相关。

“When you’re doing work that could be seen as either creation or discovery, err on the side of discovery.”

当你进行的工作既可以被视为“创造”也可以被视为“发现”时,作者建议我们更倾向于“发现”的方面。这意味着,在研究或探索过程中,我们应该更多地考虑自己是如何发现或揭示已有的事实、理论或模式,而不是完全从零开始。

“Try thinking of yourself as a mere conduit through which the ideas take their natural shape.”

作者建议,我们应该将自己视为一个导管或渠道,让想法自然地流动和形成,而不是强迫或制造想法。这种看法鼓励我们保持开放和谦逊的态度,让想法自由流动,而不是试图控制或限制它们。

总的来说,这些句子鼓励人们在进行创新工作时,更加注重发现和理解现有的知识,而不是试图从头开始。这不仅可以使工作更加高效,还可以使其更有深度和意义。

(Strangely enough, one exception is the problem of choosing a problem to work on. This is usually seen as search, but in the best case it’s more like creating something. In the best case you create the field in the process of exploring it.)

Similarly, if you’re trying to build a powerful tool, make it gratuitously unrestrictive(工具越强大越好). A powerful tool almost by definition will be used in ways you didn't expect, so err on the side of eliminating restrictions, even if you don't know what the benefit will be.

当你试图构建一个强大的工具时,应该使其尽量不受限制,即使你不知道这样做的好处是什么。

我们可以分解一下来更深入地理解:

Similarly, if you’re trying to build a powerful tool, make it gratuitously unrestrictive.

词语 “gratuitously unrestrictive” 的直译是“无故地、无需原因地不加限制”。这里的意思是,即使没有明确的原因,也要使工具尽可能不受限制,为使用者提供最大的自由度。

A powerful tool almost by definition will be used in ways you didn’t expect,

这句话意味着,一个强大的工具本身的定义或特性就意味着它可能会被用于你未曾预期的方式。也就是说,真正强大的工具具有多种潜在的用途,这些用途可能超出了设计者的最初想法或预期。

so err on the side of eliminating restrictions, even if you don’t know what the benefit will be.

这部分的建议是,为了使工具能够充分发挥其潜在用途,你应该尽量减少或消除对其使用的任何限制。即使你不知道这样做的具体好处是什么,也应该这样做,因为这可以确保工具的使用不受约束,并可能产生出乎你意料的好处。

总的来说,作者建议当你创建一个强大的工具时,应该让它尽量开放和不受限制,因为这样可以确保工具的潜在价值得到最大的发挥.

Great work will often be tool-like in the sense of being something others build on. So it’s a good sign if you’re creating ideas that others could use, or exposing questions that others could answer. The best ideas have implications in many different areas.

If you express your ideas in the most general form, they’ll be truer than you intended.

True by itself is not enough, of course. Great ideas have to be true and new. And it takes a certain amount of ability to see new ideas even once you’ve learned enough to get to one of the frontiers of knowledge.

In English we give this ability names like originality, creativity, and imagination. And it seems reasonable to give it a separate name, because it does seem to some extent a separate skill. It’s possible to have a great deal of ability in other respects — to have a great deal of what’s often called “technical ability” — and yet not have much of this.

I’ve never liked the term “creative process.” It seems misleading. Originality isn’t a process, but a habit of mind. Original thinkers throw off new ideas about whatever they focus on, like an angle grinder throwing off sparks. They can’t help it.

If the thing they’re focused on is something they don’t understand very well, these new ideas might not be good. One of the most original thinkers I know decided to focus on dating after he got divorced. He knew roughly as much about dating as the average 15-year-old, and the results were spectacularly colorful. But to see originality separated from expertise like that made its nature all the more clear.

这句话 But to see originality separated from expertise like that made its nature all the more clear. 的意思是说,当我们看到一个原创的思考者在一个他并不熟悉的领域(如约会)产生的想法,尽管这些想法可能很新颖和独特,但可能并不完全正确或实用。这种情况使我们意识到,原创性(或创新性)和专业知识是两个可以分开的概念。也就是说,一个人可以在某个领域有很强的创造力,但并不意味着他在这个领域是专家。

换句话说,这句话强调了原创性和真实的专业知识之间的差异。通过这个例子,作者指出,即使某人有原创的想法,也不意味着他们的观点一定是正确或有深度的,除非这与他们的专业知识相结合。

I don’t know if it’s possible to cultivate originality, but there are definitely ways to make the most of however much you have. For example, you’re much more likely to have original ideas when you’re working on something. Original ideas don’t come from trying to have original ideas. They come from trying to build or understand something slightly too difficult.(适当难度) [15]

Talking or writing about the things you’re interested in is a good way to generate new ideas. When you try to put ideas into words, a missing idea creates a sort of vacuum that draws it out of you. Indeed, there’s a kind of thinking that can only be done by writing.

当你试图将想法表达为文字时,有时你可能会发现某些想法或信息缺失。这个“缺失的想法”在你尝试阐述它的过程中,产生了一种“真空”感。这种真空感会迫使你深入思考,从而“吸引”或激发你产生新的或更具体的想法来填补这个空白。简而言之,当你试图写下自己的思考时,你可能会更深入地思考那些以前未完全清晰或未完全形成的想法。

因此,写作有时能够引发那些仅通过思考很难产生的特定类型的思维。当你在纸上或屏幕上看到自己的话语时,可能会更容易发现逻辑上的漏洞或信息的缺失,并因此被迫进一步深入地思考和完善它。

Changing your context can help. If you visit a new place, you’ll often find you have new ideas there. The journey itself often dislodges them. But you may not have to go far to get this benefit. Sometimes it’s enoughjust to go for a walk.[16]

确实,散散步就能想到很多新的东西

It also helps to travel in topic space. You’ll have more new ideas if you explore lots of different topics, partly because it gives the angle grinder more surface area to work on, and partly because analogies are an especially fruitful source of new ideas.

探索多种不同的话题可以帮助你产生更多的新想法,部分原因是这为你的思考提供了更多的“材料”或“空间”,部分原因是类比是一个尤为有助于产生新想法的工具。

“angle grinder”原本是一种工具,用于磨削、抛光或切割材料。在这里,它被用作隐喻,代表一个人的思考和创意能力。当你给角磨机更多的表面去工作,它可以产生更多的火花或效果。同样地,当你探索更多不同的话题时,你为自己的思考和创意能力提供了更多的“材料”或“表面”,从而产生更多的新想法。

Don’t divide your attention evenly between many topics though, or you’ll spread yourself too thin. You want to distribute it according to something more like a power law. [17] Be professionally curious about a few topics and idly(无目的地) curious about many more.

Curiosity and originality are closely related. Curiosity feeds originality by giving it new things to work on. But the relationship is closer than that. Curiosity is itself a kind of originality; it's roughly to questions what originality is to answers. And since questions at their best are a big component of answers, curiosity at its best is a creative force.

这段话确实包含了一些哲学和抽象的思考,我会帮助你理解它。

“Curiosity and originality are closely related.”

这意味着好奇心和原创性有紧密的联系。好奇心驱使人们去探索、学习和尝试新的事物,而这种探索过程往往会产生新颖和独特的思考或创意。

“Curiosity feeds originality by giving it new things to work on.”

好奇心鼓励我们深入探索未知领域,为我们的原创性提供了新的素材和灵感。简单来说,好奇心为原创性“供给”新的素材或主题。

“Curiosity is itself a kind of originality; it’s roughly to questions what originality is to answers.”

这句话表达的是好奇心本身也是一种原创性的表现。好奇心会产生问题,而原创性则为这些问题提供答案。比喻地说,好奇心对于提出问题就像原创性对于提供答案一样重要。

“And since questions at their best are a big component of answers, curiosity at its best is a creative force.”

这句话进一步强调了问题的重要性。好的问题本身是答案的一个重要组成部分,因为它们指引和驱动了我们的思考和探索。因此,当好奇心处于其最佳状态时,它就成为了一个强大的创造性动力。

即:由好奇心出发得到的答案往往会具有原创新.

Part 4

自信地裁剪:不要因为对某物自豪或为其付出了巨大的努力就留下它,即使它不合适。追求本质:将工作简化至其核心,结果会更加纯粹,更容易理解。

数学与艺术的优雅:艺术中的优雅与数学中的优雅紧密相连,优雅往往超出了数学的范围。

优雅与努力:虽然繁琐的解决方案可能短期内更受认可,但真正优雅的工作可能看起来不需要那么多努力,因为它已经存在。

创造与发现:当你无法确定你是在创造还是发现时,更多地考虑自己是发现的一部分。

工具的力量:创建强大的工具时,应尽量消除限制,使其在未预见的方式上发挥作用。

重要性的创意:伟大的创意常常像工具一样,其他人可以基于此构建。

原创性的本质:原创性不仅仅是一个过程,它是一种思维习惯,不依赖于某个领域的专业知识。

提高原创性:工作、写作、交流、改变环境、探索不同的主题都可以激发原创性。

好奇心与原创性:好奇心和原创性紧密相连,好奇心本身就是一种创新;好奇心对问题的态度与原创性对答案的态度相似。

将以上的信息总结成一个凝练的短语, 或者短句, 结尾配上一个emoji.给我四个版本.

Having new ideas is a strange game, because it usually consists of seeing things that were right under your nose. Once you’ve seen a new idea, it tends to seem obvious. Why did no one think of this before?

When an idea seems simultaneously novel and obvious, it’s probably a good one.

Seeing something obvious sounds easy. And yet empirically having new ideas is hard. What’s the source of this apparent contradiction? It’s that seeing the new idea usually requires you to change the way you look at the world. We see the world through models that both help and constrain us. When you fix a broken model, new ideas become obvious. But noticing and fixing a broken model is hard. That’s how new ideas can be both obvious and yet hard to discover: they’re easy to see after you do something hard.

One way to discover broken models is to be stricter than other people. Broken models of the world leave a trail of clues where they bash against reality. Most people don’t want to see these clues. It would be an understatement to say that they’re attached to their current model; it’s what they think in; so they’ll tend to ignore the trail of clues left by its breakage, however conspicuous it may seem in retrospect.

To find new ideas you have to seize on signs of breakage instead of looking away. That’s what Einstein did. He was able to see the wild implications of Maxwell’s equations not so much because he was looking for new ideas as because he was stricter.

The other thing you need is a willingness to break rules. Paradoxical as it sounds, if you want to fix your model of the world, it helps to be the sort of person who’s comfortable breaking rules. From the point of view of the old model, which everyone including you initially shares, the new model usually breaks at least implicit rules.

Few understand the degree of rule-breaking required, because new ideas seem much more conservative once they succeed. They seem perfectly reasonable once you’re using the new model of the world they brought with them. But they didn’t at the time; it took the greater part of a century for the heliocentric model to be generally accepted, even among astronomers, because it felt so wrong.

Indeed, if you think about it, a good new idea has to seem bad to most people, or someone would have already explored it. So what you’re looking for is ideas that seem crazy, but the right kind of crazy. How do you recognize these? You can’t with certainty. Often ideas that seem bad are bad. But ideas that are the right kind of crazy tend to be exciting; they’re rich in implications; whereas ideas that are merely bad tend to be depressing.

There are two ways to be comfortable breaking rules: to enjoy breaking them, and to be indifferent to them. I call these two cases being aggressively and passively independent-minded.

The aggressively independent-minded are the naughty ones. Rules don’t merely fail to stop them; breaking rules gives them additional energy. For this sort of person, delight at the sheer audacity of a project sometimes supplies enough activation energy to get it started.

The other way to break rules is not to care about them, or perhaps even to know they exist. This is why novices and outsiders often make new discoveries; their ignorance of a field’s assumptions acts as a source of temporary passive independent-mindedness. Aspies also seem to have a kind of immunity to conventional beliefs. Several I know say that this helps them to have new ideas.

Strictness plus rule-breaking sounds like a strange combination. In popular culture they’re opposed. But popular culture has a broken model in this respect. It implicitly assumes that issues are trivial ones, and in trivial matters strictness and rule-breaking are opposed. But in questions that really matter, only rule-breakers can be truly strict.