China's young want to work 经济学人精读 Economist

本站

背景音乐可左下角暂停,下方是该篇文章的朗读版音频,有需求可以播放(如果不能显示,可以点击链接:网易云_China’s young want to work):

The job search goes on

China’s young want to work.

For the government Youth unemployment is now shockingly high

CHINA IS A land of remarkable statistics. But an official figure published on May 16th still managed to stand out. The unemployment rate among China’s urban youth, aged between 16 and 24, exceeded one in five in April.

The figure boggles the mind(让人难以置信) for a variety of reasons. China is running short of young people. It is trying, without much success, to raise the birth rate. Its economic future hangs on(取决于) increased education, which could improve the quality of its workers even as their quantity declines. China is also famous for mobilising resources, including manpower. Yet it is wasting large numbers of the best-educated cohort(人才) it has ever produced.

“Hang on”是一个非常多功能的短语,根据上下文它可以有多种意思。例如:

等一下: “Hang on a minute!”

依赖: “Our decision hangs on the results of the survey.”

坚持: “Just hang on, help is on the way.”

词汇的含义经常是基于其历史和文化的背景演变的。”Hang”原意是”悬挂”,而”on”可以表示方向或依附。从字面意思上来看,“悬挂在…上”可能指的是物体或事情的存续、持续或依赖于另一物体或情况。例如,一个画像挂在墙上,它的位置依赖于墙。这样的直观含义可能使”hang on”逐渐与”依赖”或”取决于”的意思联系在一起。

Youth unemployment is puzzling, as well as surprising. It has increased even as China’s economy has reopened after the sudden end of its zero-covid regime in December. It has jumped up(大幅上升) while the overall unemployment rate has edged(小幅下降) downwards (from 6.1% in April 2022 to 5.2% a year later). And it is likely to rise further in the next few months. This year, a record 11.6m students will graduate from university, an increase of almost 40% since 2019. They include Wang Lili, who will leave one of China’s top-100 universities this year with a degree in management. “The market is terrible,” she laments. “Many graduates are very anxious.”

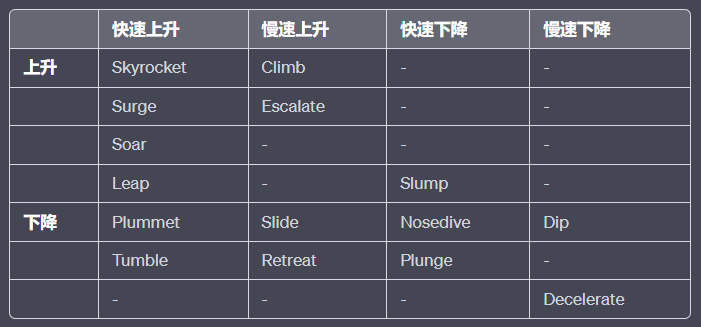

Spiral: 可以表示迅速上升or下降

The number of unemployed youth (about 6.3m in the first three months of this year) is small relative to China’s 486m-strong(逾) urban workforce. But they attract most of the attention, points out(指出) Xiangrong Yu of Citigroup, a bank, and his colleagues. The anxiety and disappointment felt by college students—and spread through social media—could “affect the confidence of the entire society”, write Zhuo Xian and his co-authors at the Development Research Centre (DRC), a government think-tank(智库).

Although the problem has outlasted(still exists even after) the pandemic, it is partly caused by it. When covid struck, many Chinese chose to extend their studies. In 2020, for example, the Ministry of Education told universities to increase the number of Master’s students by over 20%. That has created a bulge of(激增) newly minted(新出现的/刚刚产生的) graduates entering the labour force in subsequent years.

China’s reopening may have tempted many of those who had dropped out of the job market to re-engage before firms were ready to hire them. The bottleneck has been aggravated(加剧) by mismatches in timing, skills and aspirations. Some graduates delayed their job hunt last year to prepare for entrance exams for higher degrees or the civil service. But employers last year wanted to fill their ranks(填补员工队伍) early because of fears of a winter covid wave. So later job-seekers missed the best recruitment months and many are now competing for the same jobs as students leaving university in 2023.

(因此,后来的(而不是后来)求职者错过了最好的招聘月份,许多人现在都在竞争与2023年大学毕业生相同的工作。)

这句话是说,当中国重新开放时,许多之前退出工作市场的人可能被吸引回来并重新参与到求职中,即使公司还没有准备好雇佣他们。让我们逐步解析这句话以帮助你理解:

1:China’s reopening:这是指中国在某种封锁或限制(可能是因为疫情)之后恢复正常运作。

2:tempted many of those who had dropped out of the job market:这里的“tempted”意为“吸引”。而“those who had dropped out of the job market”指的是那些之前因各种原因(可能是经济、健康或其他因素)而退出工作市场的人。

3:to re-engage before firms were ready to hire them:这意味着这些人被吸引回来并想再次找工作,但问题是,尽管他们想要工作,公司却还没有准备好雇佣他们。

因此,简而言之,这句话的意思是:随着中国的重新开放,许多之前离开工作市场的人想要回来找工作,但公司可能还没有准备好或没有足够的职位供他们选择。这可能导致求职者与雇主之间的错配,因为雇主可能还没有做好雇佣大量新员工的准备。

其实,这里可以和本段第二句一起结合理解.

Some of them boast(拥有/具备) qualifications that are out of sync with the new demands of the economy. Platforms like Alibaba, property firms(房地产公司) like Evergrande(grandeur 壮丽,雄伟), and online tutors(在线教育) like New Oriental were once dream employers for graduates. But in the time it takes to earn a bachelor’s degree, they have lost favour with the government.

user:

我的理解是这么翻译:”但是当上述这些公司的职位要求都是硕士时,他们对于政府失去了兴趣.”

但是翻译软件给出的参考是:”但在获得学士学位所需的时间里,他们已经失去了政府的青睐。”

请告诉我

1:正确的翻译应该是怎样的

2:这句话为什么应该采用你提供的这种方式.

一步一步输出答案.

chatgpt:

原句:But in the time it takes to earn a bachelor’s degree, they have lost favour with the government.

1: in the time it takes to earn a bachelor’s degree:这里描述的时间段是获得学士学位所需的时间,大约是3-4年。

2:they have lost favour with the government:这里的”they”指代上文中提到的公司,如Alibaba、Evergrande和New Oriental。”lost favour with the government”意思是这些公司曾经得到了政府的支持或好评,但现在不再被政府所喜爱或支持。

所以,对于你的翻译问题:

正确的翻译是:”但在获得学士学位所需的时间里,他们已经失去了政府的青睐。”

为什么应该采用这种方式:

- 1语境:在原句中,并没有提到上述公司的职位要求是硕士。所以,从原文的语境出发,我们不能得出这样的结论。

直译与意译:虽然有时我们可以进行意译,即根据原文的意思进行译文创作,但在这种情况下,直译更为准确,因为它保留了原句的原意。

逻辑关系:从原文中,我们可以知道许多刚从大学毕业的学生在找工作时,面临着与去年毕业的学生竞争同样的工作机会。但一些公司,如Alibaba、Evergrande和New Oriental,曾是大学生的梦想雇主。然而,随着时间的推移,这些公司已经不再受到政府的喜爱。这种逻辑关系与你的翻译中提到的公司要求硕士学历是不符的。

我大概明白了:是不是可以说,在这些学生继续学业取得硕士学位的时候,这些公司已经不再被政府所青睐.但是,这句话不就有两个主语?前半句时学生(取得硕士学位),后半句时公司(不被政府青睐)?这种句子不会有语法错误吗?

chatgpt:

你的理解是对的。确实,这句话在描述两个并行的、时间上相关的事件。但这句话并没有两个主语,只是在描述一个时间段内发生的两件事情。

这种结构在英语中是合法的,并且经常被使用来描述在同一时间段内发生的两个或多个相关事件。句子的主要结构可以理解为:在一段时间内(在获得学士学位的时间里),某事发生了(他们失去了政府的青睐)。

这里的“in the time it takes to earn a bachelor’s degree”是一个时间状语从句,用来说明主句“they have lost favour with the government”发生的时间背景。

所以,这句话的结构在英语语法中是完全正确的。

“boost” 和 “bolster” 这两个词都有增强或提高的含义,但它们在使用和语境中有所不同。以下是这两个词的定义和区别:

Boost:

定义:给予提振或增加;推动。

用法:通常用于描述某种突然的或显著的提升或增加。

示例:The advertisement campaign helped boost the sales of the product.

Bolster:

定义:支持或加强;巩固。

用法:通常指为了给某物提供稳定性或支持而增强它。

示例:He provided additional evidence to bolster his argument.

总结:

Boost 更偏向于描述一个积极的、快速的增长或提升。

Bolster 更多地强调提供稳固的支持或加强。

boast: 拥有/夸耀

China’s leaders now fear what they call the “disorderly expansion of capital”(资本无序扩张) in sectors(领域) like property and education, as well as the market power and cultural reach(文化影响力) of tech firms. Recruitment has therefore slowed. Only 5.5% of students graduating this year expect to go into the education and training industries, according to a survey by Zhaopin, a recruitment portal.

Some graduates now adopt a “spray and pray”(盲投) approach, as Ms Wang (not her real name) puts it, submitting applications willy-nilly. The government is keen to steer talent into “hard tech” industries, such as aerospace, biotechnology and electric vehicles. They are promoted in the latest five-year plan and have grown faster than industry as a whole, says Louise Loo of Oxford Economics, a consultancy. Employment may follow. According to the recent Zhaopin survey, 57% of engineers graduating this year had already received a job offer, compared with only 41% of their counterparts(相对应的/相似的,此处指毕业生) in the humanities(人文学科).

“Willy-nilly” 原本是“will he, nill he”的缩写,直译为“他愿意,他不愿意”,表示不管某人是否愿意,某事都会发生。这个短语的使用可以追溯到14世纪。现在,“willy-nilly”通常用来描述某事是随机、没有计划或是必然的。

例如,在您提供的句子中,“willy-nilly” 表示应届毕业生随意、无计划地提交工作申请,而不是根据特定的工作或兴趣进行选择。

从词源和历史背景来看,”willy-nilly” 的起源并不是为了描述随机或无计划的行动,但随着时间的推移,它的用法已经演变,现在更常用来描述这种行为。

One of the oddities(奇怪现象) of China’s labour market is that less-educated youth are less likely to be unemployed. Youngsters with vocational qualifications(职业资格证书) or just a high-school education may have more practical skills and a more burning need(迫切的需求) for a job. “Everyone says a degree is a stepping stone,”(open sesame 敲门砖) said one hapless(倒霉的) graduate in an online comment translated by China Digital Times, a media-monitoring website, “but I’m slowly coming to realise it’s more like a pedestal I can’t get down from.”

这部分揭示了该毕业生的感受。这里的“pedestal”可以理解为一个高高的基座或者柱子。一旦站上去,很难再下来。这意味着,尽管他有一个学位,这个学位反而成为了限制他的一个因素。他可能发现自己因为学位而被限制在某种特定的角色或期望中,而无法获得那些需要实际技能或不同技能的工作机会。

Students’ aspirations may be changing. The proportion choosing to continue their studies (at home or abroad) fell by almost half in this year’s Zhaopin survey. Students are also keen on stability and security. The share who rank(~ as first choice:将..作为首选) state-owned enterprises(国有企业) (SOEs) as their first choice has increased for three years in a row(连续) to 47%, compared with 27% who favour a foreign-financed or domestic private firm(国内民营企业). The remaining quarter wish to work for the government or public institutions.

The government’s response to record youth unemployment may reinforce(加强) these trends. The State Council(国务院), China’s cabinet(内阁), has urged local governments to recruit as many graduates as their budgets allow. It has also called on enterprises to create at least 1m internships for unemployed youth, in return for(以换取) subsidies(补贴) and tax breaks(税收减免). The offer is open to all firms, but SOEs are most likely to heed the call(听指令,heed the call of duty). These initiatives(举措) risk drawing some of China’s better-educated minds into some of the least efficient parts of its economy.

But for young folk, stop-gap(权宜之计,临时解决方案) measures do at least alleviate(减轻) some of the worry and confusion. Ms Wang, for example, has combined her studies over the past two years with an internship at a foreign firm. That gave her “something to do every day”, she says, and also led to a satisfying job

offer—in human resources. With luck, she will enjoy a long career helping China use those resources better. ■

词源和历史背景:

“Stop-gap” 这个词组由两部分组成:“stop” 和 “gap”。其最初的含义与其字面意思相符,即“阻止”(stop)一个“缺口”或“间隙”(gap)。它最初用来描述一个物体,如一个塞子或楔子,用于暂时封闭一个开口或裂缝。

这个词汇最早的使用可以追溯到16世纪的英格兰,那时它主要被用作名词。在那个时期,人们可能会用物理的“stop-gap”来阻止液体泄漏或保持风不进入某处。

演变和引申含义:

随着时间的推移,这个词的用法从物理的“封堵物”扩展到了更抽象的含义,开始用于描述任何临时解决方案或权宜之计。例如,如果一个公司的员工突然离职,而公司又急需找人填补这个空缺,他们可能会雇佣一个临时工作人员作为“stop-gap”,直到他们找到一个长期的替代者。

在现代英语中,“stop-gap”经常用于描述这种非永久性、快速但可能不完美的解决方法或策略。

总之,“stop-gap”这个词汇从其最初的物理意义逐渐演变为描述任何临时解决方案或策略的词汇。

chatgpt:

尽管Ms Wang只是一个在外国企业工作的人力资源部员工,但她却被期待能够“帮助中国更好地利用其人力资源”。这种描述似乎暗示了一个讽刺的事实,即中国,一个庞大的国家,目前可能并没有最佳地使用其巨大的人力资源,而Ms Wang,作为一个单一的个体,却被寄予了为整个国家在人力资源方面做出改变的希望。这在某种程度上显得有些夸张和讽刺,因此,从这种视角看,该句可能具有黑色幽默的成分。

但是,即使Ms Wang在一个外企的人力资源部门工作,她仍然可以为中国的人力资源做出贡献。这表示,每一个个体,无论其位置如何,都有可能对更大的社区或国家产生正面的影响。此外,她的职位确实为一个年轻人提供了就业机会,从而在一定程度上缓解了就业市场的压力。这句话也同样具有积极性、希望和每个人的潜在价值。

Subscribers can sign up to Drum Tower, our new weekly newsletter(简报), to understand what the world makes of(看法) China—and what China makes of the world.