New research helps explain why Chinas low birth are stuck 经济学人精读 Economist

本站

背景音乐可左下角暂停,下方是该篇文章的朗读版音频,有需求可以播放(如果不能显示,可以点击链接:网易云_China’s young want to work):

New research helps explain why China’s low birth rates are stuck

Spillover effects may be to blame

THE SCARS(伤疤) left by China’s population-control policies are clear. Last year, its population started to fall for the first time since 1962; its working-age population has been declining for a decade. A shrinking workforce acts as a drag(拖累了) on growth, and a swelling number of elderly puts pressure on the welfare system(福利体系).

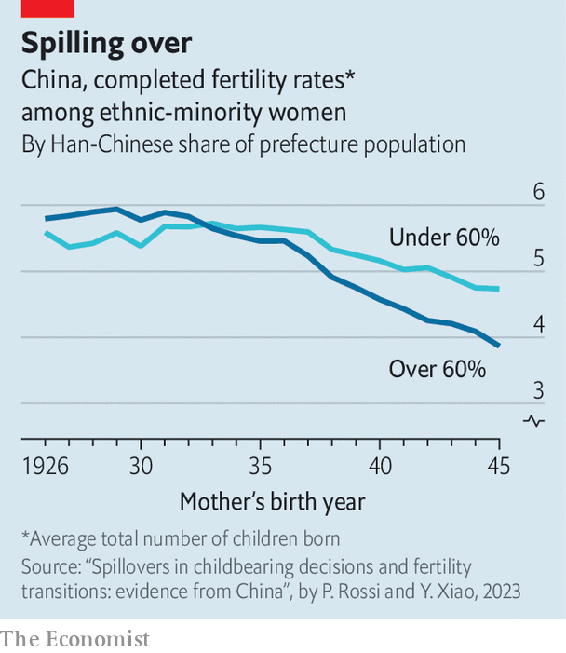

Family-planning(生育政策) regulations like the one-child policy are widely blamed for depressing birth rates. But a less explored idea is that falling birth rates can ripple through the population(在群体中产生连锁反应) causing the decline to be self- reinforcing(这个现象会对现象本身产生正反馈而加强/恶性循环). There has been little hard evidence to back this up, but a new paper about changes in China 50 years ago appears to offer some proof. Pauline Rossi of Ecole Polytechnique in Paris and Yun Xiao of the University of Gothenburg show(发表文章称) in the Journal of the European Economic Association that birth-control policies have “spillover effects”, meaning that if some couples reduce their number of children, it may lead others to follow suit(效仿).

When one company introduces a new product others often follow suit.

Professors Rossi and Xiao examine fertility data for women born between 1926 and 1945. This cohort was of reproductive age(处于生育年龄) when the “later, longer and fewer” (LLF) campaign of the 1970s, the first of China’s family-planning policies, began. It encouraged couples to marry later, wait longer between children and have fewer of them. Much of China’s fertility decline happened during this period. In 1969, the total fertility rate (the average number of children a woman is expected to have over her lifetime at current birth rates) was 6.2, according to the World Bank; a decade later, when the one-child policy was introduced, it had already fallen to 2.7.

Crucially(重要的是), the LLF campaign targeted only the main ethnic group, the Han. That allowed the authors to study how ethnic-minority groups, who were exempt from(豁免) it, responded. After controlling for other factors, they found that the policy did not affect minorities who lived apart from the Han. For those who lived among the Han, however, it led to a decline in fertility— what the authors suggest is evidence of spillovers(溢出效应). The greater the share of Han in the prefecture(县,居住区), the stronger the effect.

Spillover effects may work in two ways. First, couples who have fewer children have more resources to invest per child. Other couples may feel compelled(有必要/被迫) to emulate(效仿) them if they want to compete, especially in areas such as education. A second way is through social conformity(从众). As some couples have fewer children, this may influence others to limit the number of children they have, too. The authors found that minorities culturally closer to the Han were affected more by the LLF.

China is not the only place affected by spillovers. They have been found in South Korea, too, another country with a low fertility rate and punitively expensive education. Many children there attend private tuition classes, known as hagwon, late into the evening. Seongeun Kim of Sejong University and others found that when wealthy families spent less on private classes, it led lower-income families to do the same. Spillovers may happen where people have strong economic or social incentives to keep up with others.

“Spillovers” 在这里意味着某种行为或决策的影响从一个群体“溢出”到另一个群体。在这个上下文中,富裕家庭的消费决策产生了一个“溢出”效应,影响了低收入家庭。原因可能是人们有很强的经济或社会动机去跟上其他人。例如,如果一个社区中的多数家庭都停止发送他们的孩子去参加昂贵的私人课程,那么其他家庭可能也会觉得不应该是唯一继续支付这种费用的家庭,因为这可能在社交或文化上被视为“与众不同”或“浪费”。

人群的从众心理是一个复杂的现象,其背后有多种心理、生物学和社会学原因。以下是一些可能导致从众心理的原因及其底层逻辑:

生物学原因:从进化的角度看,成为一个社群的一部分可以提高生存和繁殖的机会。古代的人类依赖团体来共同狩猎、搜集食物和防御外来威胁。因此,适应并融入大多数人的行为和信仰可能是一种生存策略。

对认同的需求:人类有一种天生的需要,那就是被社区或团体接受和认同。从众可以使人感到更加安全,减少被排斥或孤立的风险。

信息不确定性:当个体不确定自己的决策或看法时,他们可能会依赖其他人的意见和行为。这被认为是一种“社会证明”,即如果多数人都这么做或这么认为,那么它可能是正确的。

减少心理不适:与大多数人持有相反的观点或行为可能会带来心理不适或紧张。从众可以避免这种不适,使人感到更加舒适和自在。

社会压力:在许多文化和社会中,不从众可能会带来直接的后果,如被嘲笑、被排斥或其他形式的惩罚。

从众心理的底层逻辑主要围绕人的社会生物学需要,以及在一个群体中寻求安全、接受和认同的需求。然而,这种心理也有其缺点,例如可能导致团体思维或阻碍创新。尽管如此,在许多情境中,从众心理是有益的,可以帮助维持社会稳定和和谐。

For China, the implications are grim(影响是严峻的). The government has belatedly tried to prod couples into(鼓励) having more children, with little success. Even though the one-child policy ended in 2016 and China switched to a three-child policy in 2021, birth rates have not rebounded. The fertility rate fell to 1.2 in 2021, a record low. The high cost of having children means couples want fewer of them. Low birth rates are in turn reinforced by spillovers, leading more couples to follow suit. Without `external impetus(动力)`, China cannot escape this trap.

What can be done? Theoretically, if spillovers work in reverse, getting one segment of the population to have more children could have an impact. To this end(为此), China’s leaders have tried to crack down on private tutoring(打击私人辅导) in order to slow the education arms race. They could also incentivise(激励) couples through payments(奖励) or benefits for extra kids. But experience suggests that such policies yield meagre results(收效甚微). China is finding that it was much easier to use force to restrict the number of births than it is to increase it. ■

Subscribers can sign up to Drum Tower, our new weekly newsletter, to understand what the world makes of China—and what China makes of the world.